“The Lords of their Majesties privy Councille Doe Hereby recommend To the Commissioners of their Majesties Thesaurie To Cause payment be made to Serjant Mcphersone and Serjant Edermonstrong of the reward offered to the seasurs [seizers] of Tinker Scarlat, presently prisoner in the Tolbooth of the Cannongate, if any such reward hes been offered; and if none such be offered Then to cause payment be made to them of such a competent rewaird as their Lordships shall think reasonable for seizing of the persone of the said John Scarlat, Tinker, in respect these two serjants have seazed him”

6 December 1694, NRS, PC1/50/62-63

I hunted for John Scarlet during my PhD research. A bigamist thief and “Egyptian” (traveller) who somehow became employed as a bodyguard for militant field preachers John Welsh and Richard Cameron, Scarlet was captured in 1679 after violently killing a foot soldier near Loudhon Hill, Ayrshire. I had come to assume that Scarlet had probably died in Edinburgh Tolbooth, where he was still being held in February 1681,[1] deported, or perhaps even executed outside of the capital. Somewhat unsurprisingly, given the unsavoury and un-‘saintly’ aspects of his characterisation, Scarlet isn’t mentioned in the texts that memorialised the activities of Cameron and other ‘covenanting’ nonconformists during the Restoration period. His only real mention is in Robert Wodrow’s The History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland, where Scarlet is salaciously described as “a notorious Rogue” who travelled “about the Country” with “Six or Seven Women whom he termed his Wives.” Always looking to clean up the image of southwestern nonconformity, Wodrow firmly condemns “this Villain Scarlet” as “the Actor” of tasteless violence “that suffering Presbyterians cannot be charged with.” “Indeed,” Wodrow stated, “all good Men must lo[a]the such a Wickedness.”[2]

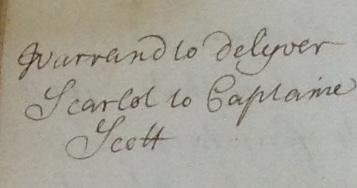

Then, photographing manuscripts for The Scottish Privy Council Project, I spotted Scarlet’s name. Alive – contrary to my previous assumptions – and apparently still kicking well enough for privy councillors to subsequently order on 26 February 1695 that he be exiled overseas as a soldier in royal service.[3] Freshly re-captured as a notorious bandit, was this really him? So many years later, could this be a son? The description of this John Scarlet as a “man of infamie” suggests it was not. So, where had he been? Jailbreaks were common, which might explain his liberty, but why would he still be hunted with promise of a reward so many years after the major shift in regime and political priorities wrought by the 1688-1690 ‘Glorious’ revolution?

The order that Scarlet be sent abroad as a soldier perhaps suggests an element of lenience. The decision was also very common in 1690s Scotland. Desperate to fill the levies of both soldiers and sailors set by King William for his continental wars, Scottish privy councillors routinely permitted convicts to fight rather than face condemnation. To the same end, they also ordered frequent roundups of “sturdie beggars, idle vagabonds” and “vagrant persones who cannot give a rationall account of their constant residence”.[4] John Scarlet, as a traveller, may well have been included in such a pursuit. Often known as ‘Egyptians’, little is known about Scotland’s travelling community at this time, its members often only appearing in records only when deported or executed. Could both the rumours about Scarlet’s personal conduct and his treatment by privy councillors reflect contemporary assumptions based on this marginality? Or do they reflect a very singular individual?

Quite unusually, and without explanation, the councillors then took back their instructions for Scarlet’s military service. Just two days later, on February 28 1695, “the order formerlie given” regarding Scarlet was revoked and the Privy Council instructed that a forger named Thomas Anderson be sent in his place. Scarlet himself was now to be tried for his “villanies” by their Majesties’ Advocat, Sir James Stewart of Goodtrees, before the High Court of Justiciary. It is not clear why such a change of heart took place. Nor why on 3 April some felt compelled to prompt action from Goodtrees, who was also a member of the Privy Council, and “verballie recomended” that he either decide to finally send Scarlet “to Flanders as a souldier or otherwayes to pursue him for his crymes.”[5]

In the end, Scarlet was tried and next appears in the books of Privy Council during January 1699 after petitioning against a death sentence for robbery. Following a temporary delay and additional petitions, Scarlet was then reprieved after volunteering for banishment: this time to the North American plantations. Promising never to return “on pain of death” and carried “in irons” to a waiting ship at Leith, Scarlet then vanishes from the historical record.[6]But Scarlet continues to remind me that whilst the 1688-1690 Revolution is often seen as a watershed moment, which left the 1680s I researched for my PhD thesis fairly detached and disparate from the 1690s I now examine as a postdoctoral researcher, there are endless threads of continuity. Among the councillors who discussed Scarlet’s fate on the day he is last mentioned was John Campbell, 1st earl of Breadalbane, who also served on the Privy Council under the ousted James VII & II. Meanwhile, Stewart of Goodtrees, exiled and excluded from political influence during the Restoration era, was most definitely present in another way as a leading theorist of covenanting thought. Goodtrees’ Jus Populi Vindicatum (1668) asserted nonconformists’ right to self-defense and was often used by militants, like Cameron, to justify violence against representatives of the state. Does this explain the Advocat’s potential reluctance to try Scarlet for his crimes? Above all, ongoing attention to a man like Scarlet, whose social marginality continued uninterrupted by political revolution, testifies to the Privy Council’s enduring and extraordinary reach into the lives of ordinary people.

Dr Laura Doak (Research Fellow)

[1] ‘Edinburgh Tolbooth ward and liberation book, 1679-1688’, NRS HHII/6/176.

[2] Robert Wodrow, The History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland (Edinburgh: James Watson, 1721-1722) ii, pp.25-26. Much of Wodrow’s language and information stems from a series of contemporary letters he collected that detailed Scarlet’s escapades. These are now in the National Library of Scotland: NLS Wod. MS Folio XXVI, cli-cliii.

[3] NRS, PC1/50/134.

[4] i.e. NRS, PC1/47/582.

[5] NRS PC1/50/139-140.

[6] NRS PC1/51/520-521.